When automotive engineer Andrew Lawrence was commissioned in 1940 to design an air pistol that would be powerful, accurate, inexpensive to manufacture and would replicate the balance and handling of a firearm, he came up with an innovative design that resembled both the Colt Woodsman and the Luger. However, wartime shortages meant that the result of his work, the Hy-Score air pistol, didn’t finally appear for sale until 1946. These spring powered air pistols proved to be reliable and well made and they became enormously popular and many hundreds of thousands were produced until new safety rules in the US led to the end of production in 1968.

Relatively recently, people have started to appreciate just how innovative and well-made the Hy-Score was and these pistols are starting to become sought-after collector’s items. But, what’s the story behind the Hy-Score and would you really want to add one of these to your replica collection?

Development

Entrepreneur Steven E. Lazlo started the S.E. Laszlo House of Imports of Brooklyn, NY in 1933. His plan was to create an American company through which he could import and market some of the best products from Europe. He was very successful in this and quickly began to import large numbers of airguns, telescopes, binoculars, lenses and other items. The market for European airguns in pre-war America was particularly strong with the imported products (especially those from Germany and the UK) being regarded as being of higher quality than home-grown American airguns. It didn’t take Lazlo long to realise that there would be a ready market for an American manufactured airgun which was made to the same quality standard as the guns he was importing.

In 1940 he approached his brother, Andrew Lawrence (Andrew had anglicised his surname to the more American sounding Lawrence in 1939) with a design brief for a spring powered air pistol which included seven main requirements:

- Ease of cocking.

- Minimum muzzle velocity of 300fps (for .22” version) and 400 fps (for .177” version).

- Elimination of parts needing frequent replacements such as leather seals, etc.

- Trigger pull not to exceed 3½ pounds and to be short and crisp.

- Barrel to be rifled for accuracy.

- Appearance and balance to approximate as closely as possible that of a standard firearm.

- Low manufacturing cost by use of stampings, automatic screw machine parts and plastics.

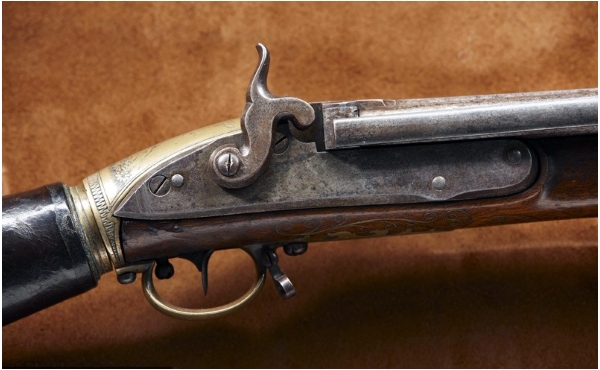

Andrew, a talented automotive design engineer, began his design study by looking at some of the imported air pistols that Steven Lazlo was selling in order to assess their designs. He examined two German Air pistols, a Haenel and a Diana, as well as a Swedish Zenit and a British Webley. All were spring powered designs with various methods of cocking. However, after considering the relative merits of each, Andrew produced a design for something very different, a concentric piston design where the air piston fits round the outside of the barrel. This allows the main spring and barrel to be long (increasing power) but because these are concentric, it also keeps the overall length of the pistol short. This wasn’t the first time that this design had been used for an air pistol – the British Westley Richards and Abas-Major air pistols for example had used a similar overall design. However, this was the first time that an attempt had been made to combine this design with modern production methods to produce an air pistol constructed using pressed steel to ensure that it looked and handled like a firearm.

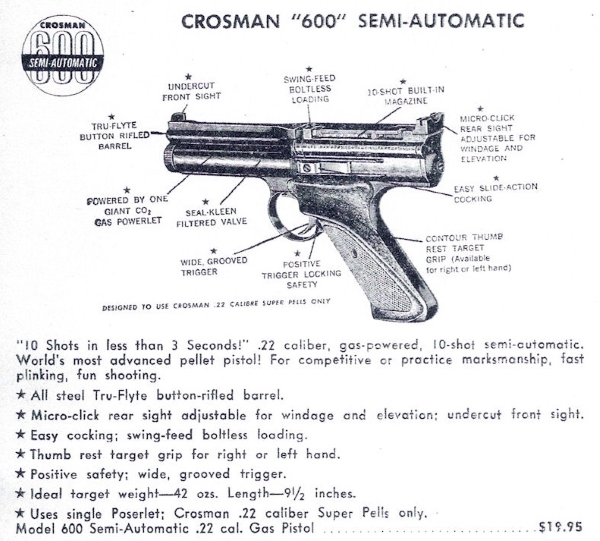

The unusual design of the Hy-Score was mentioned a lot in early advertising.

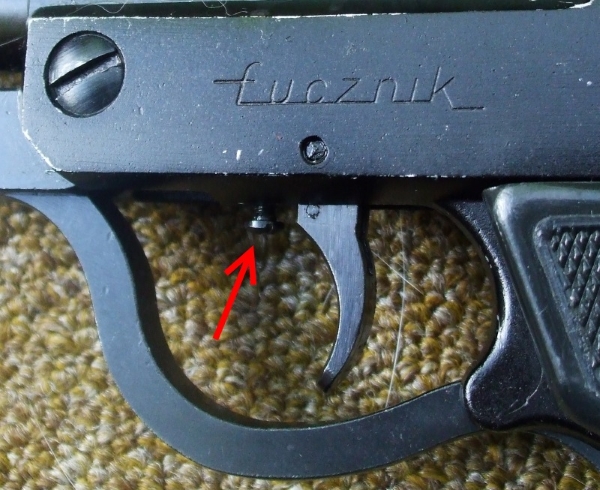

Lawrence also included other innovative ideas in his design. For example, most contemporary air pistols used leather for seals, but this tended to dry out and required frequent lubrication to keep it working efficiently. Instead, steel piston seals were to be used on the new design (though, in the event, these proved to be too brittle to withstand the forces in an airgun compression chamber and these were fairly quickly replaced with neoprene O rings). The grips were to be made of Tenite, a new plastic material developed by the General Electric Company which was hoped to be both strong and durable. The grip design incorporated the insertion of two large steel slugs to ensure that the completed pistol had good balance. The trigger design was also novel – to avoid the full weight of the mainspring bearing on the sear (which would have increased pull weight), Lawrence designed what he called a “servo mechanism” which knocked the sear free as the trigger was pulled, giving a much lighter trigger action. There was also a “dry fire/practice” facility which allowed the trigger to operate without the pistol being fully cocked, so that shooters could get used to the trigger pull. Even the loading gate used a unique and clever “camera shutter” mechanism that ensured effective sealing while being reliable and simple in use. Cocking was achieved by lifting the compression cylinder, breech and barrel from the rear and rotating this assembly round a pivot pin in front of the trigger guard.

The completed air pistol certainly looked like nothing else on the market. In contrast to most other contemporary air pistols, with its blued finish and chunky looks, it did look and handle like a firearm, most notably like the iconic German Luger even if it wasn’t intended to be a direct replica of that pistol (though later Hy-Score advertising proudly claimed “the accuracy of an air rifle with the looks and handling of a Luger”). By around 1942, the design was ready to go into production, but by that time America was involved in World War Two and the US War Production Board cut off the supply of raw material to all production that was not considered essential for the war effort, including the manufacturing of air pistols.

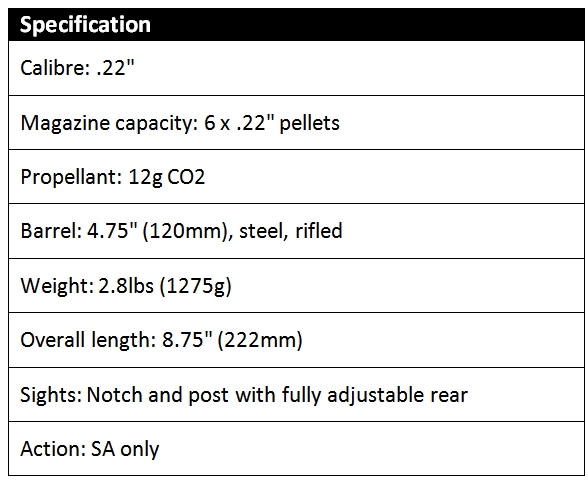

For this reason, it wasn’t until 1946 that Steven Lazlo was finally able to begin advertising what had been named the Hy-Score Target Model Air Pistol through the newly created Hy-Score Arms Corporation. The first models (no model numbers were initially assigned) were single shot only and offered in both .177’ and .22” calibre, but it wasn’t long before Andrew Lawrence began refining the design to produce a multi-shot version. This used a magazine on the end of the pistol which incorporated six pellet chambers. When the user turned the breech cap, one of the chambers would line up with the breech, dropping a pellet into position.

Production

1949 advertising for the Hy-Score from Popular Mechanics Magazine. “Looks and feels like a Luger. Revolutionary mechanism blasts pellets at close-to-firearm speed!”

Production of the first Hy-Score Target Model began in 1946 and this air pistol immediately proved to be powerful and reliable and became popular with air pistol enthusiasts across America. From 1948 onwards, single shot Hy-Score pistols were provided with a longer barrel and a revised rear sight and were designated as the Model 800 (the earlier models were then referred to as the Model 700). The Model 800s also used revised production methods so that they required less final machining, though some people feel that the extremely high quality of the first models was reduced with the Model 800. When the repeating version was introduced, this was designated the Model 802. And if you’re wondering, the Model Number 801 was given to a Hy-Score, break-barrel air rifle.

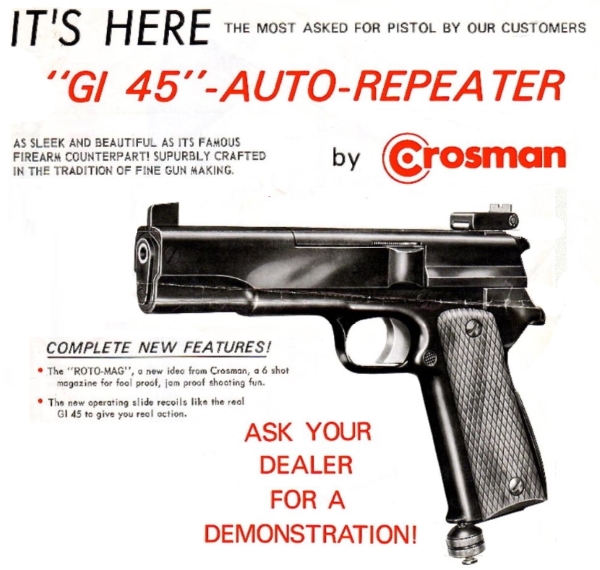

Advertising for the Model 802 repeater, also from 1949

The original Model 700 had incorporated a relatively short barrel with an extended outer barrel shroud. In 1952, the Hy-Score company began to produce the “Sportster” and “Shorty” Models 803 and 804 (the 803 Sportster was a single shot version, the 804 Shorty was a repeater). These used the short barrel of the original Model 700 with a shorter outer barrel. These models were often sold with interchangeable .177” and .22” rifled barrels and a smoothbore barrel for BB shooting. However, these short-barrelled versions were less powerful and less accurate than the longer barrelled 800 and 802, and proved to be less popular. Confusingly, there was also a Hy-Score 805 Pocket Model (despite the fact that Hy-Score already had a Model 805 in their range – a licensed version of a break-barrel Diana air rifle). It appears that the Model 805 is basically a .177” calibre Model 803 with a fixed, non-interchangeable barrel though these appear to be very rare. By the end of 1954, production of all short barrelled versions had ended and only the Model 800 and 802 remained in production.

Many hundreds of thousands of Hy-Score pistols were produced in America between 1946 and 1968, when all production ended. Most were Model 800 or 802. Production ended mainly because the Hy-Score was not provided with any form of manual safety and Andrew Lawrence believed that the trigger design of the Hy-Score would make it difficult to incorporate such a device without a major re-design. Increasingly strict safety laws in the 1960s in America meant that there was a limited future for any air pistol which didn’t have a manual safety and so the decision was made to end production. The Model 802 ceased production first and for a time, only the Model 800 continued. Then this too ended in 1968 and Steven Lazlo went back to selling imported air guns (though Hy-Score continued to sell accumulated stocks of the Model 800 up to 1970).

The Hy-Score company went into liquidation in 1981 following the death of Steven Lazio in 1980, but that wasn’t quite the end of Hy-Score production. In 1989 a British businessman, Richard Marriot-Smith, bought not only the rights to manufacture the Hy-Score but many of the machine tools and jigs required. These were shipped to Kent in England and the Phoenix Arms Corporation was set up to manufacture and sell a slightly revised version of the Model 800. This incorporated an improved rear sight which was adjustable for elevation, a thicker, heavier machined front end and a barrel that was approximately 8” long and recessed about ½ from the muzzle for a threaded section which was used to mount a silencer. The Phoenix Hy-Score also had a revised body which incorporated milled grooves to allow the fitment of a telescopic or laser sight. Sold as the Hy-Score Sporter, these air pistols were supplied with interchangeable .177” and .22” barrels and an optional silencer. Initially, only a single shot version was produced but, in September 1990, a repeater version was introduced which was based on the Model 802. At around the same time, a new, fully adjustable plastic rear sight was added and versions with this feature are generally referred to as “Mark II” models, though otherwise they are identical to the first models. Sporters were supplied either in blued finish with brown plastic grips or in chrome finish with white or grey grips. However, the Hy-Score Sporter still lacked a manual safety which meant that it couldn’t be sold in many markets. Limited opportunities for sales meant that by 1991, all production of the Phoenix Hy-Score pistol had ended.

The American Hy-Score was confidently advertised in the 1940s as “the world’s most powerful air pistol.” By the time that the Phoenix Hy-Score Sporter was advertised in 1989, it had been downgraded to “one of the world’s most powerful air pistols’”

Design

The basic design of the Hy-Score didn’t really change much from the first version produced in 1946. On the very first versions, the rifled barrel was actually only 7¾” long, but this was hidden by using a longer, drawn steel outer shroud. From 1948 onwards, Model 800 and 802 Hy–Scores had a longer, 10¼” rifled barrel which was virtually as long as the outer shroud. From the time that these models were introduced until production ended twenty years later, their design remained almost unchanged. The Sportster and Shorty and Pocket Model versions (Models 803, 804 and 805) introduced in 1952 used the 7¾” barrel from the original models with a shorter outer barrel.

Model 803 Sportster

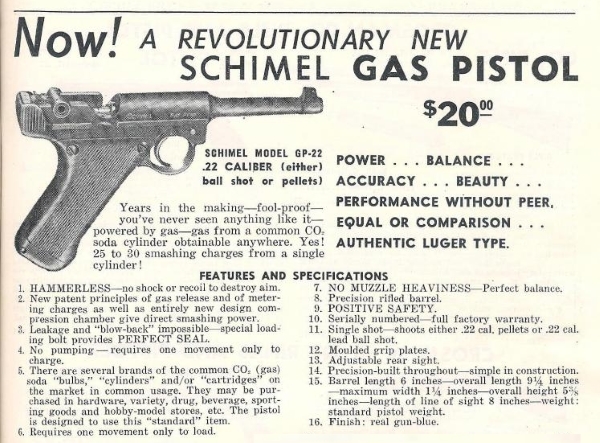

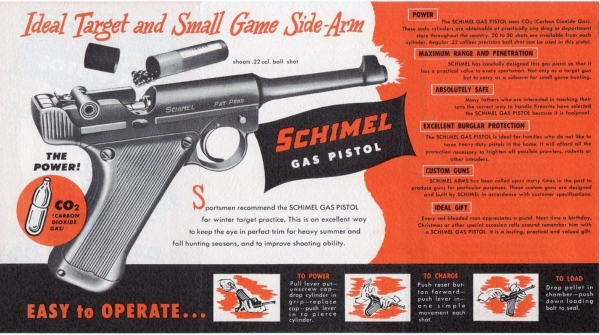

The frames on all versions of the Hy-Score are made from pressed steel which means that they can be blued, unlike more modern replicas which are made from zinc alloy. Likewise the body tube which is made from drawn steel. And that, in most cases, is what you get on the Hy-Score – a durable, hard wearing, glossy blue/black finish that lasts approximately forever. The newest Hy-Scores (other than the Phoenix versions) were made almost fifty years ago, but most seem to have retained their finish well. The same goes for the Tenite plastic used for the grips. Unlike the material used, for example, on the grips for the Schimel which was produced around the same time, the grips on the Hy-Score seem to resist cracking and shrinkage very well. Some Hy-Scores were also produced with a rather nice chromed finish and white plastic grips, and this too lasts well.

When the Phoenix Arms Company re-launched the Hy-Score in 1989, there were a number of differences. The rear sight was improved and in the Mark II version replaced with a more robust and fully adjustable plastic “field sight”. The inner rifled barrel was shortened (compared to the Model 800 and 802) and the barrel shroud was threaded for an optional silencer which was claimed both to reduce noise and to act as a cocking aid. The barrel shroud itself and the front of the frame were redesigned and machined rather than pressed to give a much more chunky look. However, in terms of mechanical function and operation, the Phoenix Hy-Scores are identical to the US models.

Phoenix Hy-Score Sporter Mark II

Shooting the Hy-Score

To prepare any Hy-Score for shooting, you must first cock the gun and compress the mainspring. To do this, the latch on the right side of the frame, above the trigger guard, must be pushed forward to release the upper part of the pistol. Then, the whole upper body is pivoted forward around a pin in front of the trigger guard. A link in the frame drags the piston forward and compresses the mainspring until it catches on the sear with an audible “click.” The upper body is then pivoted back until it latches closed. With the pistol cocked, you do have to very careful about avoiding accidental discharge given the lack of any form of manual safety. It’s also said that striking any Hy-Score model at the rear of the receiver even fairly gently or dropping it will cause the pistol to fire so some caution is required when handling a cocked Hy-Score.

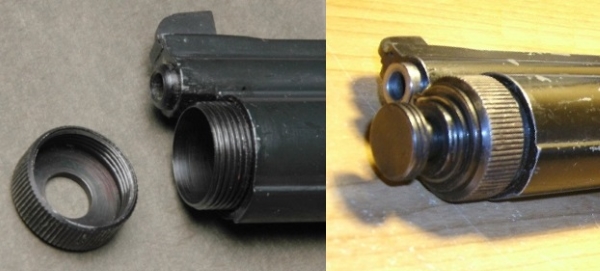

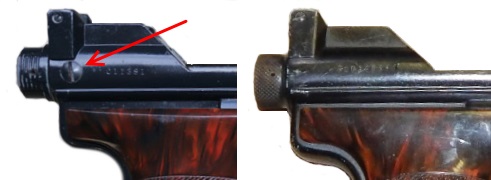

To load a pellet (in the single shot version) the pistol must be pointed down and then the knurled breech cap is turned anti-clockwise to open the central breech shutter. A pellet is then dropped into the opening in the end cap, point down. The end cap is then turned clockwise to allow the pellet to drop into the breech and tightened to seal the breech. In the repeater, the process is similar, other than that up to six pellets can be loaded into the breech cap which is then rotated, with the pistol pointing down, to load a single pellet into the breech for firing.

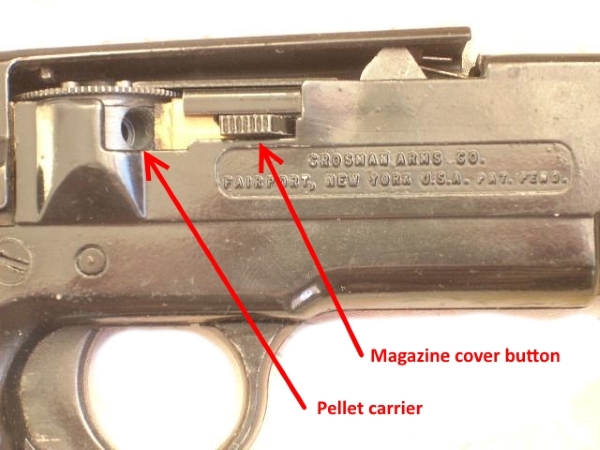

There is just a single opening in the centre of the breech cap on single-shot models

Incidentally, don’t be fooled by the “Repeater” tag – the Hy-Score Models 802 and 804 aren’t like, for example, the Crosman Model 600 which will fling a stream of pellets downrange as quickly as you can pull the trigger. The loading process on the repeaters is finicky, they seem choosy about pellet type and of course they must still be cocked for each shot. In fact, many people seem to prefer the simplicity of the single shot models which, they claim, can be shot just as quickly as the repeaters.

The breech cap on the repeater is a much more complex design

With the Hy-Score cocked and with a pellet loaded, you’re ready to fire. And it seems that there is a great deal of disagreement about this part of the Hy-Score experience. Andrew Laurence claimed that the Hy-Score was designed and tested to give groups of 1” or less at a range of 30ft using standard pellets, but that improved accuracy could be obtained by using competition grade pellets. Some owners agree, claiming that the Hy-Score is very accurate. Others claim that groups of 2½” or more at 30 feet are much more likely. Lawrence also claimed around 300fps for the .22” version and 400fps for the .177” version and most tests of longer barrelled versions do seem to agree with these power figures. In general, the Model 800 and 802 with their longer barrels are more powerful and accurate than the Models 803, 804 and 805. Most reports suggest that the Phoenix Hy-Scores are just as powerful and accurate as the 800 and 802 and some accounts even suggest that it was necessary to reduce power on these versions to meet UK power limits.

There seem to be two issues affecting accuracy with the Hy-Score (assuming that the pistol and barrel are in good condition). First is the trigger action – it’s long and creepy with a vague release point. Presumably this is a result of the servo mechanism, but it’s certainly much less crisp and light than many other contemporary classic air pistols. The second issue is the action of the air piston. This slams to the rear when the trigger is pulled and results in a forward reaction in the spring housing, causing the muzzle to dip down just as the pellet is being fired. The sights are designed to compensate for this (the barrel actually points well above the point of aim), but the amount of dip depends on your grip and stance – some people find that it works well, others that the point of impact is well above or well below the point of aim.

The Hy-Score is a fairly hefty air pistol, weighing around 2.2 pounds (1000g), but it is nicely balanced and the grips suit right and left handers. It’s pleasant to shoot, but, if you’re thinking about buying one of these, you may want to try it first. Some people report very good accuracy, some people report average accuracy at best. There are certainly bound to be variations between individual examples of any elderly air pistol, but this one seems also to depend on shooting technique. If possible, try before you buy.

Buying a Hy-Score

If you decide that you do want to buy a Hy-Score, the good news is that there are lots about and this generally seems to be a well made, well finished and reliable air pistol. If you compare it to, for example, the Schimel, another Luger lookalike launched at about the same time, the materials used on the Hy-Score appear to be of much better quality and it’s relatively easy to find a Hy-Score in good condition. The bad news is that this pistol is now becoming recognised as a classic and prices for good examples have risen dramatically in recent years. Highest prices seem to be for the very first Model 700s, especially those which come in their original boxes. The Shorty, Sportster and Pocket Models also command high prices because of their relative scarcity with the chromed versions being most sought-after. Cheapest currently seem to be the Model 800 and 802, but then these are probably the most powerful and accurate of the US Hy-Scores so they’re ideal if you want a replica you can shoot as well as admire.

In reliability terms, the only real problem is the relatively fragile rear sight fitted to all US Hy-Scores. On many examples this breaks off and finding a replacement may not be easy. Other than this, and the need to replace the neoprene O ring piston seal now and again, there is very little that seems to go wrong with Hy-Scores. Finish seems to last very well indeed, the Tenite grips don’t seem prone to shrinking or cracking and there don’t appear to be any inherent mechanical weaknesses.

The Phoenix Hy-Score Sporter was often sold as a kit which included two barrels (in .177” and .22” calibres) and a silencer in a foam lined hard case

The British-made Phoenix Hy-Scores seem to be, if anything, even better made than the US versions. The rear sight is certainly much more robust on the Sporter Mark II and the quality of pressing and machining is very good indeed. The main problem is that relatively few Phoenix Hy-Scores were made in a period of not much over one year of production, so finding one of these won’t be easy and will likely cost you as much if not more than a US made Hy-Score.

Conclusion

The Hy-Score represents innovative design coupled with very high standards of production and finish from the Golden Era of American air pistols. It may not be capable of the sort of pinpoint accuracy that some other contemporary replicas provide, but it’s a robust and reliable air pistol that just seems to go on shooting without problems for year after year. If you want a classic replica which you can shoot without worrying about whether it’s going to break (I’m looking at you, Crosman 451!), you are probably going to want one of these in your collection. Just don’t wait too long – the way that interest in the Hy-Score is increasing, it’s going to get harder and harder to find a pristine example for reasonable money.

Related Pages

Links

Short article from 2006 about the Hy-Score on the Pyramyd Air Blog site

The Hy-Score on Trev’s Airgun Scrapbook